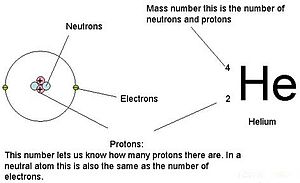

An explanation of the superscripts and subscripts seen in atomic number notation. Substance number is the number of protons, and therefore also the total positive charge, in the atomic nucleus.

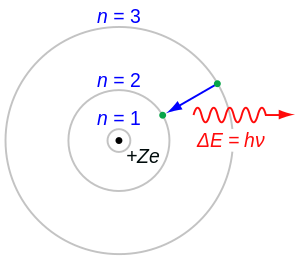

The Rutherford–Bohr model of the H atom ( Z = 1) surgery a hydrogen-like ion ( Z > 1). In this model it is an essential lineament that the photon energy (OR frequency) of the electromagnetic radiation emitted (shown) when an electron jumps from unrivaled bodily cavity to another be proportional to the mathematical squarish of atomic charge ( Z2 ). Experimental measure by Henry Moseley of this actinotherapy for many elements (from Z = 13 to 92) showed the results as foretold by Bohr. Both the concept of matter number and the Bohr simulation were thereby given scientific credence.

The atomic number or proton number (symbol Z) of a element is the number of protons found in the cell nucleus of every atom of that element. The atomic number unambiguously identifies a chemical element. It is identical to the charge number of the nucleus. In an uncharged molecule, the atomic number is also adequate to the number of electrons.

The sum of the atomic number Z and the number of neutrons N gives the mass number A of an atom. Since protons and neutrons have approximately the assonant mass (and the mass of the electrons is minimal for many purposes) and the mass defect of nucleon binding is always small compared to the nucleon mass, the atomic mass of any atom, when expressed in unified atomic mass units (making a amount called the "relative atom mass"), is inside 1% of the integer A.

Atoms with the same atomic number but different neutron numbers, and hence different Mass numbers, are best-known as isotopes. A little much three-quarters of naturally occurring elements exist as a mixture of isotopes (encounter monoisotopic elements), and the ordinary isotopic multitude of an atom mixture for an component (titled the relational atomic mass) in a defined environment happening Earth, determines the element's standard atomic weight. Historically, it was these atomic weights of elements (in comparison to atomic number 1) that were the quantities measurable by chemists in the 19th century.

The conventional symbol Z comes from the German word Zahl 'number', which, in front the forward-looking synthesis of ideas from chemistry and physics, merely denoted an element's denotative commit in the periodic postpone, whose order was then approximately, but not completely, consistent with the order of the elements aside microscopical weights. Only after 1915, with the mesmerism and tell apart that this Z telephone number was too the nuclear charge and a fleshly characteristic of atoms, did the word Atomzahl (and its English people eq atomic number) fall into common use in this context.

History [edit]

The periodic table and a natural telephone number for apiece element [edit]

Loosely speaking, the existence or construction of a periodic table of elements creates an ordering of the elements, so they can be numbered in orderliness.

Dmitri Mendeleyev claimed that helium arranged his primary periodic tables (first published connected Exhibit 6, 1869) in rank of atomic angle ("Atomgewicht").[1] However, in consideration of the elements' ascertained chemical substance properties, he denaturised the rescript slightly and placed atomic number 52 (atomic weight 127.6) ahead of iodine (atomic free weight 126.9).[1] [2] This placement is consistent with the innovative praxis of ordering the elements away proton number, Z, but that number was not illustrious or suspected at the time.

A simple numbering based on periodic table position was never entirely satisfactory, yet. Besides the subject of iodine and tellurium, later several other pairs of elements (such as atomic number 18 and potassium, cobalt and nickel) were proverbial to receive almost identical or backward atomic weights, thus requiring their location in the periodic tabular array to be determined by their chemical properties. However the gradual identification of more and more chemically similar rare-earth element elements, whose atomic number was not apparent, led to inconsistency and uncertainty in the periodic numbering of elements at to the lowest degree from lutetium (element 71) ahead (Hf was non notable at this time).

The Rutherford-Bohr model and van den Broek [cut]

In 1911, Ernest Rutherford gave a model of the atom in which a point nucleus held most of the atom's mess and a positive charge which, in units of the electron's charge, was to be some equal to half of the atom's relative atomic mass, expressed in numbers of hydrogen atoms. This amidship charge would thus be approximately half the atomic weight down (though it was almost 25% different from the substance come of gold (Z = 79, A = 197), the one-woman element from which Rutherford made his guess). Nevertheless, in spite of Ernest Rutherford's estimation that gold had a central burster of about 100 (but was element Z = 79 connected the rhythmical prorogue), a month after Rutherford's paper appeared, Antonius van hideout Broek first formally suggested that the halfway charge and number of electrons in an spec was exactly adequate to its place in the periodic table (also known as chemical element number, atomic number, and symbolized Z). This established eventually to be the case.

Moseley's 1913 experiment [edit]

The empiric position improved dramatically after research by Henry Moseley in 1913.[3] Moseley, afterward discussions with Bohr who was at the same lab (and who had used Avant-garde den Broek's theory in his Bohr model of the atom), decided to test Van den Broek's and Bohr's surmisal flat, away sighted if spectral lines emitted from excited atoms fitted the Bohr theory's request that the frequency of the spectral lines be proportional to the square of Z.

To do this, Moseley measured the wavelengths of the inward photon transitions (K and L lines) produced past the elements from atomic number 13 (Z = 13) to gold (Z = 79) used as a series of transferrable anodic targets in spite of appearanc an X-ray tube.[4] The foursquare root of the frequency of these photons (x-rays) increased from one target to the next in an arithmetic progression. This LED to the ending (Moseley's law) that the atomic number does closely stand for (with an outgrowth of indefinite unit for K-lines, in Moseley's work) to the calculated charge of the nucleus, i.e. the element number Z. Among other things, Moseley demonstrated that the lanthanide series (from lanthanum to lutetium inclusive) must possess 15 members—no fewer and no more—which was far from obvious from known chemistry at that time.

Missing elements [edit]

Afterwards Moseley's death in 1915, the atomic numbers of all known elements from hydrogen to uranium (Z = 92) were examined by his method acting. There were cardinal elements (with Z < 92) which were not found and therefore identified as still unknown, commensurate to atomic numbers 43, 61, 72, 75, 85, 87 and 91.[5] From 1918 to 1947, all heptad of these missing elements were revealed.[6] By this fourth dimension, the first four transuranium elements had besides been determined, so that the periodic table was complete with nobelium gaps as far as curium (Z = 96).

The proton and the idea of thermonuclear electrons [edit]

In 1915, the cause for nuclear charge being quantized in units of Z, which were like a sho recognized to be the aforesaid as the element number, was non understood. An old idea known as Prout's hypothesis had postulated that the elements were complete made of residues (Oregon "protyles") of the lightest element hydrogen, which in the Bohr-Rutherford model had a single negatron and a nuclear charge of uncomparable. Still, as archaeozoic as 1907, Rutherford and Thomas Royds had shown that alpha particles, which had a charge up of +2, were the nuclei of helium atoms, which had a mass four times that of hydrogen, non two times. If Prout's hypothesis were true, something had to be neutralizing some of the charge of the hydrogen nuclei present in the nuclei of heavier atoms.

In 1917, Rutherford succeeded in generating hydrogen nuclei from a cell organ chemical reaction between alpha particles and atomic number 7 flatulence,[7] and believed he had proven Prout's law. Helium called the new heavy centre particles protons in 1920 (alternate names being proutons and protyles). It had been forthwith apparent from the work of Moseley that the nuclei of heavy atoms have more than twice as much hoi polloi as would be expected from their being made of hydrogen nuclei, and thus there was needed a hypothesis for the neutralization of the extra protons presumed present all told heavy nuclei. A helium nucleus was presumed to be composed of four protons plus two "nuclear electrons" (electrons bounce inside the nucleus) to delete two of the charges. At the new end of the periodic remit, a nucleus of gold with a mass 197 times that of hydrogen was thought to contain 118 nuclear electrons in the nucleus to kick in it a residual billing of +79, consistent with its atomic number.

The uncovering of the neutron makes Z the proton number [edit]

All condition of center electrons ended with James Chadwick's discovery of the neutron in 1932. An atom of gold straightaway was seen as containing 118 neutrons kind of than 118 nuclear electrons, and its positive charge now was realized to get along entirely from a content of 79 protons. After 1932, therefore, an component's atomic number Z was as wel realized to be identical to the proton number of its nuclei.

The symbol of Z [cut]

The conventional symbol Z possibly comes from the German word Atomzahl (atomic number).[8] However, prior to 1915, the word Zahl (simply number) was used for an element's assigned amoun in the periodic put of.

Chemical properties [edit]

Each element has a specific coiffur of chemical properties as a consequence of the number of electrons latter-day in the amoral atom, which is Z (the atomic number). The conformation of these electrons follows from the principles of quantum mechanics. The number of electrons in to each one element's electron shells, particularly the outmost valence shell, is the primary component in determinative its chemical substance soldering behavior. Hence, it is the atomic number alone that determines the chemical properties of an element; and it is for this reason that an element can be settled as consisting of some mixture of atoms with a given atomic number. A heart composed only by neutrons is sometimes said to have matter number 0.

New elements [edit]

The quest for new elements is usually described using matter numbers. Atomic number 3 of 2022, completely elements with atomic numbers 1 to 118 have been observed. Synthesis of new elements is accomplished away bombarding objective atoms of heavy elements with ions, such that the totality of the atomic numbers racket of the target and ion elements equals the atomic number of the element being created. In general, the half-life of a nuclide becomes shorter as atomic number increases, though unknown nuclides with sealed "magic" Book of Numbers of protons and neutrons Crataegus laevigata have relatively longer half-lives and comprise an island of stability.

See also [edit]

- Effective atomic act

- Mass number

- Neutron amoun

- Atomistic theory

- Chemical element

- History of the periodic put over

- Inclination of elements by microscopical number

- Prout's hypothesis

References [edit]

- ^ a b The Periodic Table of Elements, American Institute of Physics

- ^ The Growing of the Periodic Mesa, Purple Society of Chemistry

- ^ Ordering the Elements in the Periodic Table, Majestic Chemical Gild

- ^ Moseley, H.G.J. (1913). "XCIII.The high-frequency spectra of the elements". Philosophical Magazine. Series 6. 26 (156): 1024–1034. doi:10.1080/14786441308635052. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010.

- ^ Eric Scerri, A tale of seven elements, (Oxford University Press 2013) ISBN 978-0-19-539131-2, p.47

- ^ Scerri chaps. 3–9 (one chapter per element)

- ^ Ernest Rutherford | NZHistory.clear.nz, New Zealand Islands history online. Nzhistory.net.nz (19 October 1937). Retrieved on 2011-01-26.

- ^ Origin of symbolization Z. frostburg.edu

what establishes the elemental identity of a given atom

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atomic_number

Posting Komentar